In the world of Continuous Improvement (CI), we operate under a pervasive myth. It is a comforting lie we tell ourselves after every successful Kaizen event and every completed project: “If we document it, they will follow it.”

We believe that once we have captured a solution on an A3, typed it into a standard operating procedure (SOP), or presented it to leadership, the job is done. We assume that the people who walk in our footsteps will naturally absorb this wisdom. We imagine a cosmic process where future employees instinctively know where to find these files, understand them, and apply them to their own work.

But if you are a CI leader concerned with the long-term impact of your work, you already know the uncomfortable truth: They don’t.

The reality is that traditional best practice management has a failure rate estimated at nearly 85%. Most organizations are not building a library of wisdom; they are building a graveyard of forgotten binders and unvisited SharePoint pages.

I once spent years building a Tier meeting structure at a global leading food manufacturing company. Upon leaving the company and returning to visit after a year, practically all of the infrastructure that I had so carefully laid had fallen into ruin. I couldn’t help reflect on all the training sessions, dealmaking with leadership, successes celebrated, and breakthrough moments I experience with the team when I was there. Then flash forward to seeing boards that had not be updated in months, now serving as nothing more than corporate wallpaper. Lean, and all of the great learnings and best practices we put in place while I was there, were lost to history from the moment I left.

If we want to secure our impact—and frankly, our job security—we need to stop treating Continuous Improvement as just a “toolkit” and start treating it as what it fundamentally is: a Knowledge Management movement.

The Concept of “Intellectual Inventory”

To understand why our best practices fail to become common practice, we have to look at them through the lens of Lean itself. One of the seven wastes (Muda) is inventory. We know that physical inventory is bad—it ties up cash, hides problems, and eventually spoils or becomes obsolete.

Yet, we treat knowledge exactly the opposite way. We “batch” information. We hold massive training sessions where we dump 40 hours of knowledge onto employees in a single week. Or we create massive repositories of best practices that sit idle on a server.,

Knowledge that is not used immediately is just “intellectual inventory.”

And just like fresh produce in a warehouse, intellectual inventory spoils. It goes bad. It becomes obsolete. When we overproduce best practices and store them without a system for immediate retrieval and application, we are creating waste. We are batching information and “pushing” it out to the organization, hoping that someone remembers it six months or a year later when a relevant problem actually arises.

But human memory is fallible, and organizational memory is even worse. As we often see in our war rooms and project bays, “Whiteboards have a serious case of amnesia.” If the system relies on human memory or manual searching to bridge the gap between a past solution and a current problem, the system will fail.

The “Ambitious Project Manager” Syndrome

Why do perfectly good solutions get ignored? Why do we see teams constantly reinventing the wheel?

To answer this, we have to look at the psychology of the people driving change in your organization. Let’s look at a typical scenario. You have a young, ambitious Operations Manager or CI Lead. They are likely early in their career. They are eager to prove to their bosses that they are creative, intelligent, and capable of driving value.,

When this person is assigned a project, they have a chip on their shoulder. They want to leave their unique fingerprint on the organization.

Here is what they are not going to do: They are not going to spend three days mining through old slide decks, reading through reams of paper in dusty binders, or navigating the labyrinth of the company intranet to find a best practice from three years ago.

Instead, they will follow a predictable path:

- They will go observe the process themselves.

- They will talk to the operators currently doing the work.

- They will pull current data.

- They will brainstorm new solutions.

- They will execute their own plan.

In maybe 15% of cases, they might stumble across a best practice from another location or a previous year. But the vast majority of the time, they will proceed as if they are the first person to ever deal with or solve this problem.

This isn’t necessarily an act of rebellion. It is a disconnect in context. These younger leaders haven’t seen the historical cycles that older, more experienced peers have. They don’t realize that “history repeats, or at least it rhymes.” They assume that because the date has changed, or the product mix has shifted slightly, the old solutions no longer apply. They assume that what solved yesterday’s problem cannot possibly solve today’s.

The result? They spend months struggling to solve a problem that was already solved five years ago. They create chaos and turbulence, only to stick a mediocre landing, when they could have started with a world-class solution and improved it.

The Context Gap: Capturing the “Why,” Not Just the “What”

So, how do we fix this? How do we stop building “dark drawers” of forgotten projects?

The first step is to change how we document. Most best practices fail because they are documented as rigid rules rather than contextual patterns. We capture the “what” – the final countermeasure – but we strip away the context.

When context is lost, the knowledge becomes useless. A solution that worked brilliantly in 2024 might look irrelevant to a manager in 2026 because they don’t see the underlying logic.

To make best practices “stick,” we need to capture the “Why.”

We need to move toward a rigorous Case Study format. When you document a win, do not just upload the new SOP. You must capture:

- The Problem Statement.

- The Goal.

- The Results.

- The specific Conditions (Time, Place, Products).

- The “Science” behind the solution.

By capturing the science – the patterns that made the solution work – you allow future leaders to see the connection. You allow them to say, “Ah, even though we are making a different product today, the physics of this problem are the same as the one they solved last year.”

This shifts the dynamic from “following a rule” to “applying a proven pattern.” It respects the intelligence of the ambitious project manager by giving them a foundation to build upon, rather than a rigid instruction to follow blindly.

“Hidden Knowledge” Waste Calculator

The cost of re-inventing the wheel every day.

Stop “Batching” Best Practices. Start “Pulling” them.

Systematize Your Best PracticesTreat Standards as Living Organisms (The PDCA Loop)

Another reason best practices gather dust is that they are treated as statues in a museum—perfect, untouchable, and permanent.

In a true Kaizen culture, standards are made to be followed, then deviated from, then updated, then followed again.

Best practices decay without usage feedback. If a standard is two years old and hasn’t been touched, it is likely dead. The context has changed, and if the practice hasn’t evolved with it, the workforce will abandon it.

We must attach PDCA (Plan-Do-Check-Act) to our knowledge management itself.

- Plan/Do: We deploy a best practice.

- Check: Is it still working? Has a specific location found a better way?

- Act: If Location A tweaks the process and gets a 5% efficiency gain, that improvement needs to flow organically to Location B, C, and D.

Currently, this flow is blocked. Location A improves the process, but Location B continues using the old “best practice” because there is no feedback loop. We need to view best practices as living organisms that grow and adapt. The goal is not to preserve the past, but to provide a baseline for continuous evolution.

Shifting from “Push” to “Pull”: The On-Demand Revolution

The fundamental flaw in our current approach is that it is a Push System. We push training, we push presentations, and we push binders onto people who don’t currently have a problem that needs solving.

We need to transition to a Pull System for knowledge, including best practices.

We need to get the right information to the right person at the right time so they can make the right decision.,

Imagine an Andon cord. When an operator pulls the cord, help arrives immediately. We need an Andon cord for knowledge. When a project manager hits a roadblock, or when a problem-solving team enters a conference room, the relevant best practices need to be delivered then and there.

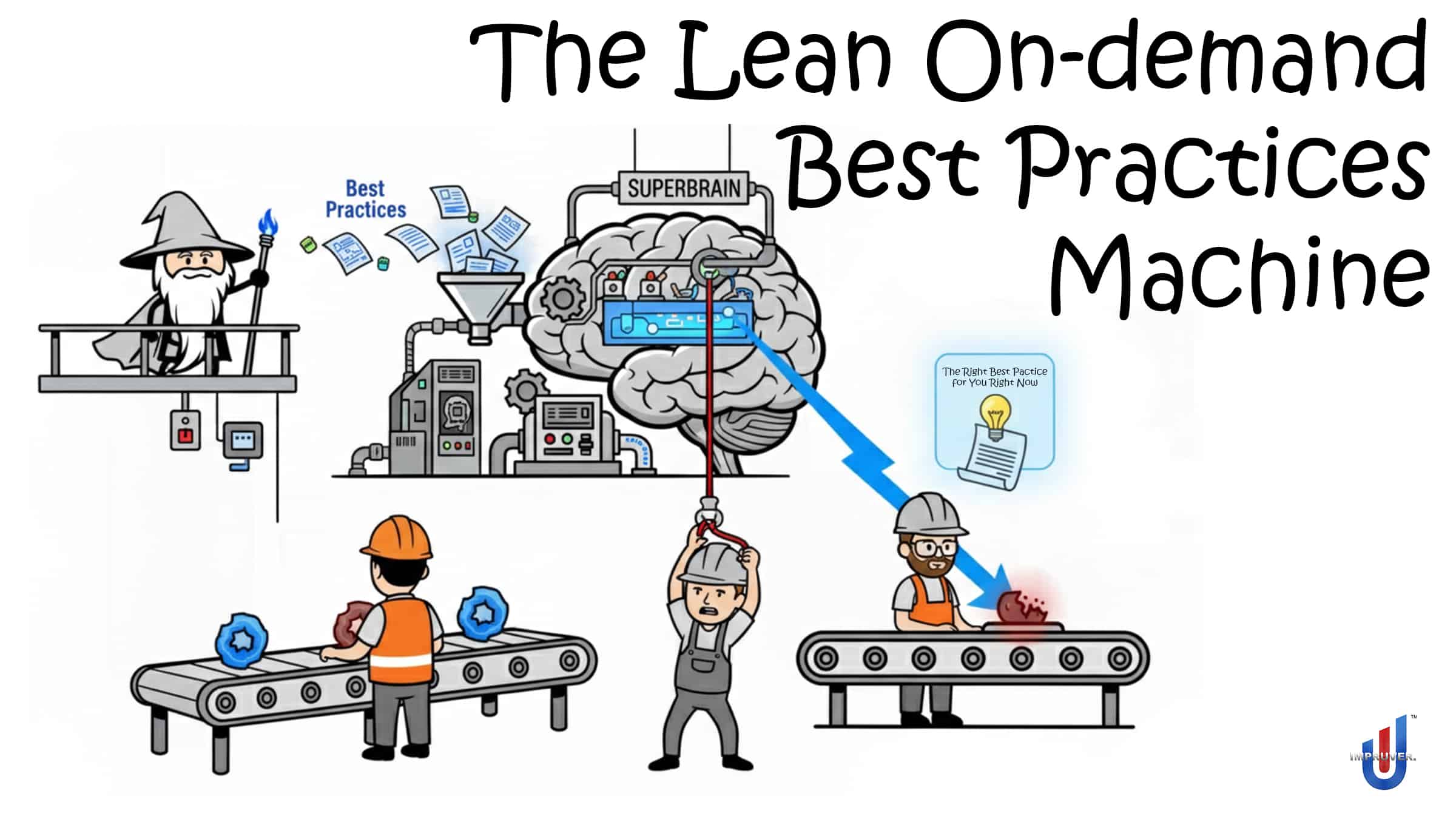

This is where we must stop working as “craftsmen” and start building a “knowledge assembly line.”

While the principles of Lean provide the framework, modern technology is the only way to scale this. We cannot rely on human memory to scan thousands of past A3s. We need a system that acts as a “Superbrain”—an active participant in our problem-solving sessions.

This isn’t about letting a computer make decisions for us. It’s about Pattern Recognition.

- A search engine (like SharePoint search) gives you a list of 50 documents and forces you to read them all to find relevance.

- A “Superbrain” system mines the history of your Five Whys, Fishbones, and SIPOCs to find the context. It says, “You are facing a quality defect in the packaging line? Here is how the Mexico plant solved that exact physics problem three years ago.”

This capability changes the role of the CI leader. You are no longer just a facilitator or a trainer. You become the architect of a system that scales intelligence across the entire supply chain. You move from isolated classrooms to a fully integrated institution of higher learning.

Conclusion: From Craftsmen to Architects

If we continue to rely on manual documentation, batch training, and static binders, our impact will always be limited by the fallibility of human memory. We will continue to see an 85% failure rate in the adoption of our hard-earned solutions.

The “Ambitious Project Managers” of the world will continue to reinvent the wheel, not because they want to waste time, but because the cost of finding the truth is too high.

It is time to clear out the intellectual inventory. It is time to stop hiding our wisdom in dark drawers. By focusing on context, embracing the living nature of standards, and utilizing systems that allow knowledge to be pulled on demand, we can ensure that the best practices of today actually become the standard work of tomorrow.

The Lean movement is, at its core, a knowledge management movement. It’s time we started managing it that way.